BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://ijmm.ir/article-1-2442-en.html

, Alireza Mortazavighahi1

, Alireza Mortazavighahi1

, Sina Habibi1

, Sina Habibi1

, Fereshteh Parto1

, Fereshteh Parto1

, Javad Allahverdy1

, Javad Allahverdy1

, Niloufar Rashidi2

, Niloufar Rashidi2

2- Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Allied Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,

Culture has always been intricately tied to the lifestyles and workplaces of people, evolving alongside their changing requirements. One global culinary tradition shared across diverse cultures is consumption of sauces besides main food. In Iran, the tradition of sauce consumption is deeply rooted with a wide array of options enjoyed by people across the country. Popular choices include mayonnaise, ketchup, chili, and white sauce, all of which hold significant appeal for the Iranians nationwide (1, 2).

These sauces are crafted from a diverse range of ingredients, including chili, onion, red and green tomatoes, and coriander (3). They are commonly paired with a variety of fast food, and a multitude of salads. The unique flavors imparted by handmade sauces make them exceptionally popular among consumers, adding an extra layer of enjoyment to their dining experiences (2, 4).

Sauces serve as valuable sources of protein, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals, with each sauce boasting its own unique set of ingredients. Each of these sauces requires specific storage conditions and exhibits varying sensitivities to environmental factors (5, 6).

Consumption of handmade sauces because of their easy access, innovative, different and interesting flavor, also new appearance is dramatically increasing day by day. Although handmade sauces are popular around the world mainly due to cheap price, there are some concerns about their hygiene and safety (2, 7). However, lack of hygienic observance during preparation, packaging, preparation of raw materials, and final product, as well as improper storage conditions such as inappropriate physical conditions including dust, contaminated equipment, insects, and unsanitary hands can cause microbiological contamination especially bacterial contamination and finally various diseases occurrence among consumers (1, 8).

As most bacteria grow in pH range 4-9, these products and their mineral compounds can provide a suitable environment for the growth of bacteria (9). The handmade sauces are mostly kept at temperature ranging from 0 to 50 and this condition as well facilitates the growth of a variety of mesophilic pathogenic bacteria, such as Escherichia coli (E. coli), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and salmonella species (10, 11). Other factors such as unsanitary vendors, improperly stored water, and uncovered containers can also be the reason for the presence of microorganisms in handmade sauces (12, 13).

Escherichia coli is a member of Enterobacteriaceae family and genus Escherichia; it is a facultative anaerobe non-sporing bacterium. These bacteria are widely distributed in the environment and contaminated food and water; the major sources on which the bacteria are spread (12, 13).

Nontyphoidal Salmonella are one of the most important zoonotic bacterial food-borne pathogens of humans. Salmonella are widely distributed in nature (14, 15) and they are the major pathogenic bacteria in humans as well as animals (16). Salmonella has been found to be the major cause of food-borne diseases and a serious public health issue in the world (17).

Staphylococcus aureus is another important bacterium in food microbiology and its presence in food products is important for the food industry, as some strains are the cause of food-borne intoxication (18, 19). They are responsible for food spoilage, reduction of food safety and shelf-life, and cause food-borne poisoning (20).

Therefore, consumption of handmade sauces containing significant amounts of these contaminations can lead to the food poisoning (21). Consuming these bacteria-contaminated products causes the onset of symptoms in a certain period of time (22), which are mainly characterized by gastrointestinal symptoms (23, 24).

Knowledge of food safety is the main key to solve problems, like food-borne diseases caused by bacterial contamination that is one of the biggest issues affecting human health and food safety (26, 27). As a result, detection of microorganisms of handmade sauces helps to protect the health of consumers (28, 29). Given the rising incidence of food-borne illnesses across the country, this study aimed to address this significant public health concern by focusing on the extent of microbial contamination in handmade sauces.

This research is particularly pertinent because such contamination poses a serious risk to consumers’ health, necessitating a thorough examination of the potential pathogens and their sources in these widely consumed products.

In this cross-sectional study, 48 different sauce samples were randomly collected from catering establishments, restaurants, and food preparation centers situated across various districts of Tehran. Samples were collected directly from the original packaging or servings provided in restaurants using sterile plastic containers with approximately 30 gr of each sauce type. Subsequently, they were promptly transported to the microbiology laboratory for the microbial examination.

Identification and Isolation of Associated Bacteria

Identification and Isolation of E. coli

The homogenized samples (10 gr) were transferred into Ringer’s solution (90 ml). Following this, 1 ml of suspension was then transferred into a tube containing Lauryl Sulfate Tryptose broth (LST broth) (Merck), accompanied by a Durham tube, and incubated at 37°C for a period of 24-48 hr. After the incubation time, 0.1 ml of suspension from the tube displaying gas production was transferred to E. coli broth (Quelab), also equipped with a Durham tube, and incubated at 44°C for 24-48 hr. Subsequently, 0.1 ml of the sample that exhibited gas production in EC broth was transferred to peptone water and subjected to further incubation at 44°C for 24-48 hr. Finally, confirmation testing was carried out using indole test (according to the national standard of Iran No. 2946).

Identification and Isolation of Salmonella spp.

The homogenized samples (25 gr) were transferred to peptone water (225 ml) and incubated at 37°C for 18 hr; a process referred to as pre-enrichment. Subsequently, 1 ml of suspension from the pre-enrichment media was transferred to 10 ml of Rappaport Vassiliadis Soy (RVS) broth (Quelab). Gray colonies observed in the RVS broth were then transferred to Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) agar (Quelab). The blue-green colonies with a black center were selected on Hectone Enteric (HE) Agar (Quelab), while colonies displaying the same color as the media, appearing transparent with a black center were chosen on Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) agar (Merck). Additionally, colorless and transparent colonies with a black center were selected on Salmonella Shigella (SS) Agar, and pink colonies were selected on Brilliant Green Agar (BG). Confirmation of these colonies was carried out through Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) Agar (Merck), Urine Agar (Merck), Indole Nitrite (Merck), Lysine Decarboxylase (Merck) Agar, and serological tests (according to the national standard of Iran No. 1810).

Identification and Isolation of S. aureus

The homogenized sample (1gr) was transferred to Giolitti-Cantoni broth (Merck) containing potassium tellurite (10 ml). This mixture was then incubated at 37°C for a period of 24-48 hr. After the incubation time, the samples were cultured on Baird-Parker agar (Merck), which includes 1% potassium tellurite and 5% egg yolk emulsion. The agar plates were subsequently incubated at 37°C for another 24-48 hr. Suspicious colonies, characterized as raised, glossy black with a narrow, transparent aura, were subjected to confirmation tests using Mannitol Salt Agar (Quelab) and the coagulase test (according to the national standard of Iran No. 6806-3).

Molecular Identification of Associated Bacteria

Conventional PCR

Total DNA was extracted from the overnight-grown pure isolates (S. aureus ATCC 33591, E. coli ATCC 11775) using DNA extraction Kit (AddBio, Korea), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity of extracted DNA samples was measured using NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo ND-ONE). The extracted DNAs were used immediately for conventional PCR or stored at -20ºC for later use. All isolates were screened for rpoB (RNA polymerase beta-subunit) and hcaTs (putative 3-phenylpropionate transporter) genes of S. aureus and E. coli by PCR amplification, respectively. The primers were designed by Primer designing tool (nih.gov) and checked using Oligo Analyzer software. The sequences are listed in Table 1. PCR products were visualized under UV transillumination after electrophoresis on 1.0% agarose gels. The associated bacteria were identified using Beacon 8 designer software.

Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed on a light cycler 96® (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), using the RealQ Plus 2x Master Mix Green (AMPLIQON, Denmark). For real-time PCR, 5 µl DNA template, 10 µl RealQ Plus 2x Master Mix Green, 1 µl of each forward and reverse primers (Table 1), were mixed and 3 µl DNase- free water was added to a final volume of 20 µl. Then, the cycling condition shown in Table 2 was conducted. Data were analyzed with light cycler 96® (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) software. Upon completion of the run, a cycle threshold (Ct) was calculated and plotted against the log input DNA to provide standard curves for the quantification of unknown samples.

Table 1. Primers specifications.

| Bacteria | Primer name | Genes | Gene Bank No | Sequence | Length | Tm | Amplicon-size |

| S. aureus | rpoBs-F | RNA polymerase beta-subunit (rpoB) | GenBank: OM994260.2 | AACACCTGAGGGACCAAACA | 20 | 60 | 314 |

| rpoBs-R | TCGCTGCTGAAACAACTTGC | 20 | 60 | ||||

| E. coli | hcaTs-F | putative 3-phenylpropionate transporter | GenBank: NC_000913.3 | GGATGACTTCGCTACCCTGG | 20 | 60 | 184 |

| hcaTs-R | TGTAGTGCACGCGATATGCT | 20 | 60 |

Table 2. Thermal profile used in Real-time PCR.

| ID | Name | Step | Cycle |

| 1 | Pre-incubation | 95°C for 5 min | 1 |

| 2 | 3 Step amplification | 95°C for 25 sec | 35 |

| 60°C for 25 sec | |||

| 72°C for 30 sec | |||

| 3 | Final extension | 5 min for 72°C | 1 |

All data analysis was performed by the statistical software SPSS16 using Fisher’s exact test to calculate the strength of association between the virulence genes and origin of the isolates, as well as different products. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Table 3. Different types of handmade sauces.

| Handmade Sauces | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Mayonnaise | 8 | 16.67% |

| Ketchup | 6 | 12.50% |

| Mustard | 8 | 16.67% |

| White | 3 | 6.25% |

| Barbecue | 3 | 6.25% |

| Soya | 1 | 2.08% |

| Sandwich | 3 | 6.25% |

| Chilly | 3 | 6.25% |

| Chocolate | 3 | 6.25% |

| Sour | 2 | 4.17% |

| Garlic | 2 | 4.17% |

| Meat | 2 | 4.17% |

| Carrot | 1 | 2.08% |

| Italian | 1 | 2.08% |

| Vegetable | 2 | 4.17% |

| Total | 48 | 100% |

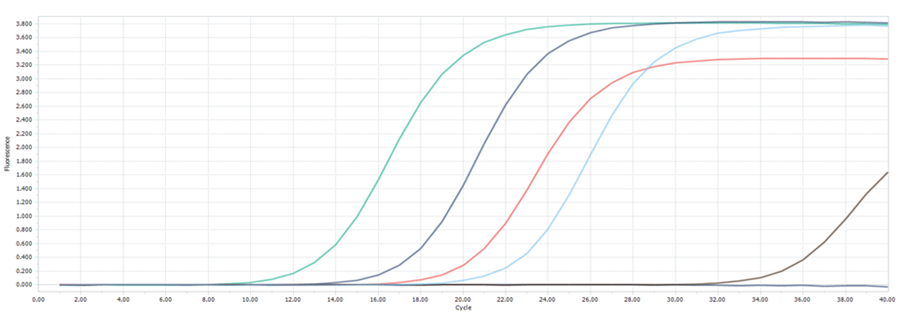

(A): Amplification curves of hcaTs gene of E. coli in samples

(B): Amplification curves of rpoBs gene of S. aureus in samples

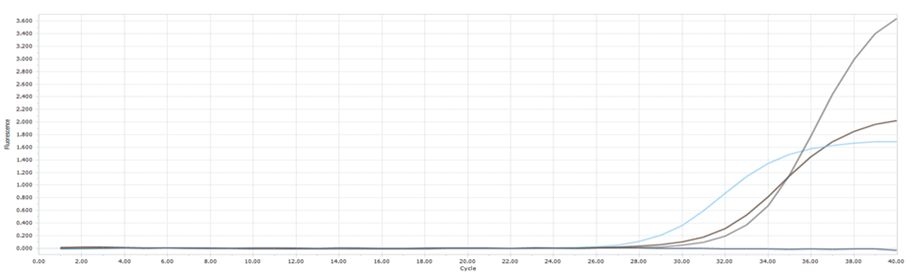

(C): Melting curves of hcaTs gene of E. coli from sauce samples and controls

(D): Melting curves of rpoBs gene of S. aureus from sauce samples and controls

Figure 1. The presence of E. coli and S. aureus in handmade sauces. It was confirmed through real-time PCR, as shown in Figures 1(A) and 1(B), respectively. The amplification curves provide the Ct values, indicating successful amplification of target DNA sequences for the identified pathogens. Furthermore, the melting curve analyses in Figures 1(C) and 1(D) validate the specificity of the PCR amplification, with distinct peaks corresponding to the target DNA melting temperatures.

The contamination rate in different types of handmade sauces was evaluated. Higher rate of contamination was seen in white (66.7%) followed by garlic (50%), mustard (37.5%), and ketchup (16.6%) sauces (Table 4). Fisher’s exact test revealed significant differences (P=0.0003).

Table 4. Summary of positive contaminated samples isolated from handmade sauces. The percentages was evaluated within

| Sauce Type | E. coli | S. aureus | Positive | Negative |

| Mustard | 3 | - | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.55%) |

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 (66.7%*) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Ketchup | - | 1 | 1 (16.6%) | 5 (83.4%) |

| Garlic | 1 | - | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) |

| Others | - | - | 0 (0.0%) | 29 (100%) |

| Total | 5 | 2 | 7 (14.5%) | 41 (85.5%) |

Bacterial contamination in 48 handmade sauce samples was evaluated for E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella spp. Using Real-time PCR method, we found that 7 out of 48 samples (14.5%) were contaminated with associated bacteria. The specific contamination rates were as follow: E. coli was detected in 5 out of 48 (10.4%); S. aureus was detected in 2 out of 48 (4.1%); and Salmonella spp. was not isolated from any of the samples.

| District | E. coli | S. aureus | Positive | Negative |

| North | - | - | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (100%) |

| West | - | - | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (100%) |

| East | - | 1 | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) |

| Center | 1 | - | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.8%) |

| South | 4 | 1 | 5 (21.7%) | 18 (78.2%) |

| Total | 5 | 2 | 7 (14.5%) | 41 (85.5%) |

Handmade sauces offer a delectable array of flavors in the culinary world and smells, enhancing meal with a personal touch. However, during the skill of sauce creation, there lies a potential concern: bacterial contamination. The presence of bacterial contaminants in handmade sauces can pose significant health risks to consumers if not properly addressed. Therefore, we delve into evaluation of common bacterial contaminants in handmade sauces, exploring their sources, impact on food safety, and strategies for mitigation. By gaining a comprehensive understanding of these contaminants, we aim to empower chefs, home cooks, and food producers with the knowledge needed to ensure the safety and quality of their handmade sauces.

In developing countries, a vast population consumes diverse food vended on the streets. These food varieties often purportedly harbor abundant spectrum of pathogenic microbial content (14). Hossain and Dey in their study revealed a substantial microorganism count in food samples spanning from 1.2×103 to 4.2×109 CFU/g (2). Furthermore, previous examinations of various street food documented elevated microbial burdens. Previous studies examining multiple street food samples have reported a substantial presence of microbial organisms (30-32).

Given the current lifestyles and dietary habits, consumers are more inclined toward ready-to-eat meals. In particular, fast food items have gained popularity due to their diverse flavors and classifications. Consumption of fast food without accompaniment of sauces, a preference particularly prevalent among younger generations, is implausible. Consumers may find themselves ingesting substantial quantities of various sauces multiple times daily in conjunction with fast food.

With increasing popularity of sauces across all age groups, it becomes crucial to conduct comprehensive studies on their qualitative attributes to elucidate the safety aspects associated with their consumption. Among these, tomato-based, white, and mustard sauces are three commonplace condiments extensively employed in consuming fast food. For example, many young children find tomato ketchup highly palatable and often consume it without additional dietary ingredients. Therefore, if their quality is low, this age group will be more susceptible to the health-related issues (33, 34).

Pathogenic microorganisms identified in sauces encompass E. coli, Lactobacillus species, Listeria species, Salmonella spp, Shigella species, Vibrio species, S. aureus, and Streptococcus species (22). Salmonella is recognized as one of the major pathogenic genera associated with foodborne bacterial outbreaks. The absence of proper heat treatment might be the cause of these contaminations, as adequate heat can effectively mitigate them (14).

Escherichia coli is a significant contributor to global foodborne illnesses, affecting individuals of all ages and demographics. The presence of E. coli serves as an indicator of fecal contamination and plays a crucial role in identifying contamination within the food supply chain, spanning from raw material acquisition to transportation of the final product. In conjunction with Enterobacteriaceae, E. coli is a crucial indicator of hygiene within food safety (2). Staphylococcus aureus food poisoning is caused by heat-resistant toxins in contaminated food, often spread by asymptomatic carriers, including food handlers. These toxins resist digestion, inducing vomiting. Despite reduced prevalence, S. aureus remains a concern, particularly in ready-to-eat food with improper storage, leading to illness (35, 36).

The present study examined 48 hand-made sauce samples from retail establishments from different districts in Tehran, Iran. Qualitative real-time PCR analysis revealed that 10.4% of samples were contaminated with E. coli, while 4.1% were contaminated with S. aureus. The remaining samples (85.5%) showed no contamination.

Our investigation indicated no contamination with Salmonella spp., however, the investigation by Islam et al (37) detected Salmonella spp. in 50% of various food samples, encompassing sauces obtained from street vendors in Dhaka City, Bangladesh (37). Furthermore, the findings of the study conducted by Hossain and Dey (2) in Bangladesh revealed contamination of all sauce samples with Enterobacteriaceae. They showed 80% of samples were contaminated with Salmonella spp (2); the rates were higher than those observed in the current investigation. Our study revealed 10.4% contamination of E. coli., however, Hossain and Dey study (2) revealed that 83.33% of samples were contaminated with E. coli. That indicated higher rates compared to our research. Our findings showed 4.1% contamination with S. aureus: only one out of six samples of ketchup sauces were contaminated with S. aureus (16%). However, in both studies by Mumtaz et al (38) and Elsayed Abdelrassoul and Mohamed Essam Eldin (12), varied reports were presented compared to our study.

In Meldrum et al (7) investigation regarding the microbiological evaluation of salad vegetables and sauces derived from kebab takeaway establishments in the United Kingdom, 5% of the 1208 sauce samples exhibited unsatisfactory microbial quality. This deficiency mainly came from E. coli, S. aureus at 102 cfu/g, Bacillus cereus, and another Bacillus spp. at 104 cfu/g. Furthermore, 0.6% of the sauce samples were deemed unsatisfactory due to Bacillus spp. at 105 cfu/g. Notably, a high percentage of chili sauce samples (8.7%) exhibited unsatisfactory or unacceptable microbiological quality compared to other sauce variants (7). In this research similar to our study, E. coli and S. aureus were the cause of handmade sauces contamination.

Ahmed et al (22), focused on the microbiological quality analysis and drug resistance patterns of bacteria present in locally produced sauces within fast food establishments in the metropolitan area of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Four categories of sauces, including tomato, tamarind, mustard, and mayonnaise sauces, were subjected to examination. The investigation revealed that all samples, except for mustard sauce, were contaminated, with total bacterial and fungal counts reaching 2.9×106 cfu/gm and 2.1×106 cfu/gm, respectively (22). Opposite to our findings that some mustard sauces were contaminated with E. coli, their mustard samples were not contaminated with any bacteria.

A study on meat demonstrated that utilization of 3% garlic induces the most pronounced inhibitory effect against E. coli O157:H7 on the third day of meat storage (12), resulting in 100% reduction. However, according to the current investigation, one of the two garlic sauces (50%) was contaminated with E. coli.

In the Fialová et al (39) study, similar to our study, there was no detection of Salmonella spp. after 48 hours incubation at 20°C. Contamination in sauces can lead to the presence of microorganisms and acidophilic fungi, which can persist and proliferate due to the nutritional properties and low pH of sauces (39).

Foodborne illnesses contribute to morbidities and death, posing a substantial obstacle to the global socioeconomic progress. Billions of people face threat of these illnesses annually, and millions succumb to disease due to the ingestion of unsafe food, leading to deaths. Annually, approximately 220 million children get diarrhea, leading to 96,000 deaths attributable to food contamination (40). The microbial contamination degree in food can escalate due to the vendor's environmental and personal hygiene practices and food handling methods (41). An investigation in Mexico suggests that consuming a single contaminated chili sauce could potentially lead to Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) disease in at least 21,000 consumers annually (5). The enforcement of strict manufacturing practices, the exercise of precise control over raw materials, and the diligent maintenance of the cold chain represent effective measures to manage or prevent microbial contamination of food.

Inculcating education and providing training for food handlers stand as critical factors in mitigating the occurrence of foodborne illnesses. Such initiatives increase awareness of microbiological food hazards, cross-contamination risks, and the importance of personal hygiene (42).

The limitation of our study was that Real-time PCR was conducted on only positive samples identified by the bacteriological method. With sufficient funding, this method could have been applied to all tested samples. Additionally, future studies with larger sample size are planned, which would provide more accurate and reliable results.

Given these conditions and limitations, it is asserted that no research of this kind combination of standard bacteriological methods and Real-time PCR technique to investigate and evaluate the contamination of handmade sauces has been conducted or designed in Iran before. Food safety plays a critical role in protecting public health by preventing foodborne illnesses, which can lead to severe health complications and even fatalities. Stringent hygiene standards across food production, handling, and storage are needed to control contaminations from pathogens. Adopting practices such as washing hands and surfaces, cooking food to proper temperatures, and preventing cross-contamination are essential to minimize risks. Regular food safety training and adherence to regulatory guidelines further ensure a safe food supply chain, promoting healthier communities.

Handmade sauces pose significant public health risks when contaminated with E. coli and S. aureus. Contamination can result from poor sanitation, contaminated raw materials, equipment, or storage practices throughout the production and supply chain. To ensure food safety, all individuals involved in production process must be trained for hygienic practices. Routine microbiological testing should be implemented at various production stages. Regular monitoring by national authorities is essential to minimize foodborne illnesses and ensure the safety of handmade sauces.

This study received financial support from the Research Council of the Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, in 2022.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR.IUMS.REC.1400.530).

Authors’ Contributions

Rashidi N. conceptualized and supervised the study. Namadi M., Habibi S. and Parto F. collected the clinical samples and conducted laboratory experiments. Mortazavighahi A. and Rashidi N. analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. Rashidi N., Namadi M. and Mortazavighahi A. made significant contributions to the study design and Rashidi N. and Mortazavighahi A. edited the manuscript.

This study was supported by Research Council of the Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Code: 1400-1-5-20927.

Conflicts of Interest

Received: 2024/07/23 | Accepted: 2025/01/12 | ePublished: 2025/01/29

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |